Supreme Court

64024-6

Carl Salts v Cliff Estes, et al

Unknown if Published

The court is asked in this case to determine if service of process upon a person who was merely looking after the defendant’s home in his absence was sufficient under our substitute service of process statute, RCW 4.28.080(15).

RCW 4.28.080(15) has remained essentially untouched by the Legislature since it was enacted in 1893. What the Legislature has not seen fit to do — change the wording of the statute – the court declined to do by judicial proclamation under the guise of liberal construction. The language of RCW 4.28.080(15), permitting service of process at the defendant’s usual abode with a person of suitable age and discretion who is then resident therein, should be enforced as it was written.

The court refused to adopt the principle in service of process that “close is good enough,” permitting service of process on virtually any person who by happenstance is present in the defendant’s home. Consequently, the court affirmed the Court of Appeals and held that a person who was a fleeting presence in the defendant’s home was not “resident” therein for purposes of RCW 4.28.080(15).

Facts

Carl Salts allegedly sustained injuries while working at the home of Cliff Estes in November of 1990. On November 22, 1993, Salts initiated a lawsuit against Estes in the Pierce County Superior Court. Eight days later, Larry Johnson, a process server with ABC-Legal Messengers, went to Estes’s home to accomplish service of the summons and complaint.

Johnson met Mary TerHorst at the front door of Estes’s home. TerHorst, who was neither related nor married to Estes, briefly spoke to Johnson; Johnson then handed TerHorst a copy of the summons and complaint, and left.

On December 6, 1993, an attorney appeared on Estes’s behalf. Subsequently, Estes moved for summary judgment, contending that service of process was insufficient under RCW 4.28.080(15) and that Salts did not commence his action within the three-year statute of limitations of RCW 4.16.080(2).

The record on summary judgment indicates the following regarding TerHorst:

- She was inside Estes’s home when Johnson arrived and she answered the door in response to Johnson’s knock.

- She was looking after Estes’s home, at Estes’s request, while Estes was out of town for a couple of weeks.

- She was at Estes’s home over the two-week period for the purpose of feeding his dog, bringing in the mail, and taking care of similar matters.

- She spent a total of one to two hours at Estes’s home between Estes’s departure on vacation and the attempted service of the summons.

- She was not the defendant’s relative or employee.

- She never lived at the defendant’s home nor did she keep any of her goods there.

- She was presented with the summons and complaint during the few minutes she happened to be in the defendant’s home one day.

Johnson also stated in his declaration, “TerHorst said that she was a resident of Cliff Estes’ abode.” TerHorst denies saying that.

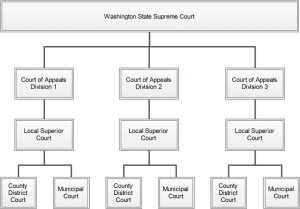

The trial court granted Estes’s summary judgment motion, holding TerHorst was not resident in Estes’s home for purposes of RCW 4.28.080(16). The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court. Salts v. Estes, No. 18415-0-II (Wash. Ct. App. Mar. 15, 1996).

The Supreme Court granted review, agreed with the lower courts, and the case was dismissed.

Specific Issues

- Does being present in the residence at the time of service constitute being a resident? No

- Are there special circumstances under which service on a visiting individual might be considered good service? Yes

- Are decisions about the validity of service fact specific? Yes

Holdings

RCW 4.28.080 (16) states that for abode service to be good, service must be made at the target’s usual place of abode to a resident of suitable age and discretion.

The statute of limitations for this case was 3 years.

The plaintiff waited until the statute of limitations was almost up before initiating the case, thereby not giving him time to correctly re-serve the documents.

Reasoning

RCW 4.28.080 describes at length how a summons may be served on a defendant. The statute generally requires personal service of a summons on the defendant, but also permits substituted personal service on the defendant “by leaving a copy of the summons at the house of his or her usual abode with some person of suitable age and discretion then resident therein.” RCW 4.28.080(16).

Thus, the statute states three requirements for a valid substituted service of process: (1) the summons must be left at the defendant’s “house of his or her usual abode”; (2) the summons must be left with a “person of suitable age and discretion”; and, (3) the person with whom the summons is left must be “then resident therein.” The service on TerHorst satisfied the first two requirements of the statute. The third element is at issue in this case.

Even those unlearned in the law would most likely conclude a house of usual abode is somebody’s home, even if only on a seasonal basis, and “then resident therein” means a person who is actually living in that house at the time of the service of process. In Wichert v. Cardwell, the court addressed the meaning of the statutory phrase “then resident therein” and concluded that the meaning of resident was too “elastic” to be of much use. To interpret the sense in which such a term is used, the court should look to the object or purpose of the statute in which the term is employed.'”

Thus, as a substitute for deciding the actual meaning of the word “resident,” the court concluded in Wichert that the legislative intent behind the substituted service statute was to provide due process, i.e., “notice and the opportunity to be heard.” The means employed must be such as one desirous of actually informing the absentee might reasonably adopt to accomplish it. Wichert seems to say it is never necessary for the substituted service to comply with the literal requirements of the statute so long as the plaintiff chooses a method of service reasonably calculated to inform the defendant of the summons. The court held in Wichert that service at the defendants’ home on the defendant wife’s 26-year old daughter, who only infrequently stayed overnight at her parents’ house, resided elsewhere, and was plainly not “then resident therein,” was sufficient.

In Sheldon v. Fettig, the court held that service on the defendant’s twelve-year-old brother at the Seattle home of the defendant’s parents at a time when the defendant was actually living in Chicago satisfied the statutory requirement that substituted service occur at a defendant’s house of usual abode. The court decided in Sheldon that “house of usual abode” means a “center of one’s domestic activity.” Thus, a person who actually lives in Chicago can maintain her “center of domestic activity” in Seattle, even if she is there only a few days a month for purposes of Washington’s substituted service of process statute. The court was able to conclude from the facts of Sheldon that the defendant was more likely to receive notice of pendency of a suit at her parents’ Seattle home, where she visited maybe four or five times a month as her flight schedule allowed, and where she did not sleep even when visiting, than in the apartment she shared in Chicago with other flight attendants.

Wichert and Sheldon mark the outer boundaries of RCW 4.28.080(16). Precious little would be left of the term “then resident therein” if the court was to determine that substitute service can be obtained on a person who happens to be in the defendant’s house only to feed the defendant’s dog and check his mail.

The court held for purposes of RCW 4.25.080(16) that “resident” must be given its ordinary meaning — a person is resident if the person is actually living in the particular home. Under no definition of “resident” found in any dictionary of the English language can any support be found for the contention that Ms. TerHorst was transmuted into a resident of the defendant’s household by temporarily feeding his dog or taking in his mail. The court declined to transform “resident” into “present” by judicial construction. The Legislature is free to amend the statute; the court is not. The Court of Appeals was correct and the Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s dismissal of Salts’ action.

C4PSE Comment

With this case the court has set some limits as to the meaning of resident, abode, residency, and other similar words. An important lesson this case teaches is that service of process is “fact specific”. This makes it difficult for the process server to decide at the door whether or not the particular set of facts he or she is faced with will satisfy the court. It is important to read both the Wichert and Sheldon cases in order to achieve an appreciation for this ruling.

When it comes to abode service, this case is considered a landmark for process servers and all professional servers should be familiar with it and aware of its implications.

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.