Summary

Gross v Sunding, 139 Wn. App. 54 Gross v Sunding (2007)

Facts:

Gross and Sunding were involved in an automobile accident in a parking lot on February 16, 2002. Gross filed suit on February 11, 2005, which was within the 3 years statute of limitations. A process server began attempting service at the Sunding residence but learned Sunding was in Oregon. The server obtained a telephone number for Sunding and spoke with him. Sunding told the server he might be returning home on March 8th.

The server began attempting at the Sunding residence again on March 8th and made multiple attempts over the next several weeks.

On May 11th (90 days after the filing date and therefore the final day to obtain service) the server spoke again on the telephone with Sunding. Sunding told the server, in vague fashion, that he would be returning home sometime during the next week to 10 days. Sunding told the server he would accept service upon his return.

The server tried several more times to contact Sunding via telephone but his calls were not returned.

On June 17th service was made on Sunding under the Nonresident Motorist Act (RCW 46.64.040) via the Secretary of State. On June 22nd Sunding filed an Answer and challenged the sufficiency of the service.

On July 26th a process server returned to the Sunding home and knocked on the door until someone answered from inside. The person inside identified himself as Sunding but refused to open the door. The server began to slide the documents under the door when they were pulled inside by Sunding. The process server advised Sunding he had been served.

On August 31 Sunding filed a motion for summary judgment alleging jurisdiction had not been obtained within the statute of limitations.

Judicial History:

Superior Court issued a summary judgment against Gross based on his failure to obtain service, and therefore jurisdiction, within the 90 day time period following filing. Court of Appeals upheld the lower courts order.

Specific Issues:

- Is untimely service of process necessarily insufficient. Yes

- Is an alternative service agreement enforceable if the time and place of delivery are not included in the agreement? No

- Is a claim of insufficient service an appropriate and sufficient defense if service did not occur within the statutory limitation period? Yes

- Do defendants have an obligation to cooperate with a process server if there is no agreement to a date, time certain, and place for service to occur? No

- Do defendants have an obligation to accommodate a process server? No

- Does a party’s failure to answer the door to accept service constitute evasion of service? No

- Does a temporarily out of state defendant’s agreement to accept service of process upon return to the state provide sufficient assurance on which a plaintiff may reasonably rely to estop the defendant from claiming untimely service or contesting the sufficiency of service of process. No

- Is whether or not a defendant has been effectively served with process a question of law for the court to decide? Yes

- Is it improper for a defendant to engage in acts which do not constitute willful evasion of process even when such acts frustrate a process server’s efforts to obtain service? No

Holdings

- Service must be made within the 90 days after filing if the statute of limitations has passed.

- Service on the Secretary of State under the Non-Resident Motorist Act, occurred over a month after the final date for service.

- The plaintiff had plenty of time to serve the Secretary of State between March 8, when the defendant was supposed to be back in town, and the deadline for service, May 11.

Reasoning

In a challenge to personal jurisdiction based on insufficient service of process, the plaintiff has the burden of proof to establish a prima facie case of proper service. Gross could not produce evidence of sufficient service; thereby failing to establish a prima facie case for proper service. Sunding and the process server never reached an agreement about an alternate time and place for delivery, only the method.

Sunding’s first estimated date of return in March was well within the tolling period. Because service around March 8 would have been timely, Gross had no reason to think that Sunding was waiving his right to timely service. The tolling period ended on May 11, the same day the process server spoke with Sunding the second time. At that point, Sunding had not accepted service and had not volunteered to, nor been requested to waive the requirement for timely service. Without knowledge about the requirements and deadlines inherent in service and the statute of limitations, Sunding could not have intentionally relinquished his right to proper service.

Gross alleged that Sunding evaded service because he failed to make himself available for service after he agreed to accept service upon his return, he would not return phone calls, he disingenuously claimed the process server had not called him after their first conversation, and he refused to open his door when the process server arrived. Sunding responded that no agreement was reached so he did not evade service. Sunding’s statement appeared to have been a verbal manifestation of his agreement to perform his duty of accepting validly tendered service. He did not create any obligation beyond this duty.

Sunding’s behavior during the statute of limitations time frame cannot be construed as evasive. Neither his trips to Oregon, nor his refusal to open the door constitute as evasion or concealment.

Gross argued that Sunding should be estopped from asserting an insufficient service defense because Sunding made promises to accept service upon his return and Gross relied upon and was damaged by those promises. Sunding responded that the telephone conversations that serve as the basis for the estoppel claim do not qualify as clear, cogent, and convincing evidence of an admission or statement required for estoppel. Gross and his counsel may have relied upon these statements, but they cannot be construed as evidence of Sunding’s agreement to accept untimely service.

Furthermore, Gross could not show reasonable reliance. Sunding apparently made a statement that he would accept service upon his return. More than a month remained of the tolling period if Sunding returned as projected on March 8th. Reliance on Sunding’s statement that he would accept service upon his return may have been reasonable in the days immediately following his expected homecoming. Even if initially Gross could have relied reasonably upon Sunding’s representations, continued reliance on the “agreement” was not reasonable in the face of repeated failed service attempts stretching for more than one month.

Gross and counsel could not have justifiably relied upon the “vague” statements made to the process server. Gross and his counsel may have inferred that this acceptance of service translated to acceptance of that service as sufficient, but this interpretation is not supported by clear, cogent, and convincing evidence. Even if Sunding agreed to accept service upon his return, he did not represent that he would not contest its sufficiency. Sunding claims that he did not know the tolling period was expiring or the legal significance of the date. Without such an understanding, Sunding’s agreement to accept service upon his return was just that – agreement to take the summons and complaint when handed to him.

C4PSE Comment

As the process server it is up to you to be aware of the service deadlines. It is also up to you to communicate with your clients. Within a week of March 8, 2005, when the defendant was supposed to be back from Oregon, the process server should have been on the phone with the client informing them of the lack of success in serving Mr. Sunding. Although it is the client’s duty to be aware of the various avenues of service available, it would have been both helpful and impressive if the process server had suggested the use of the Non-Resident Motorist Act.

Both the process server and his/her client overly relied on the telephone conversations between the server and Sunding. They assumed he was being open, honest, and that he knew more about the law than he actually did.

The plaintiff tried to convince the court that Sunding had evaded service. It is obvious from the court’s writing that it was not convinced and that it sets a high standard of proof in regards the subject of evasion of service.

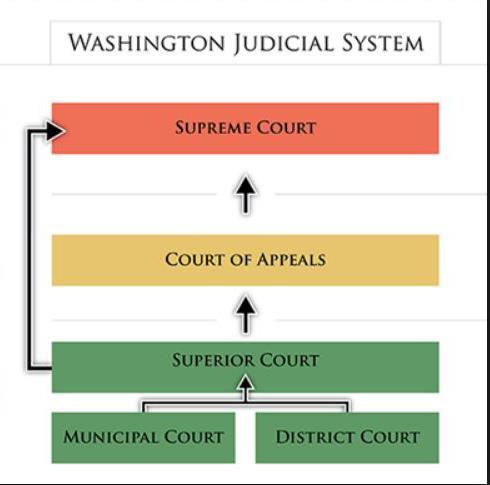

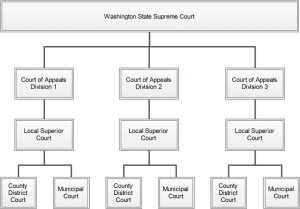

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.