Court of Appeals Division III

28817-0-III

Christopher M Farmer v Bradley M Davis and Jane Doe Davis

Published Opinion

Facts

Christopher Farmer and Bradley Davis were involved in an automobile accident on April 21, 2006 in the state of Washington. On April 10, 2009, shortly before the running of the statute of limitations, Mr. Farmer filed suit against Mr. Davis for negligence. Relying on RCW 4.16.170, which tolls the statute of limitations for 90 days upon filing suit and therefore placed the final day for service on July 9, 2009, Mr. Farmer’s counsel undertook to serve Mr. Davis.

On May 27, 2009, a process server delivered a copy of the summons and complaint to 1520 Tombstone Street, Rathdrum, Idaho, the residence address for Mr. Davis set forth in the police report of the 2006 accident. The address turned out to be that of Laurie Davis, Mr. Davis’s mother. On June 3, 2009, Mr. Davis’s lawyer filed a notice of appearance, reserving defenses for improper service and lack of jurisdiction.

Because Mr. Farmer was reportedly “concerned that the Defendant might attempt to deny [the May 27] service,” Parker Gibson, an Idaho investigator, was hired to attempt personal service on Mr. Davis. Mr. Gibson delivered a second copy of the summons and complaint to Ms. Davis at the Tombstone address on June 25. Mr. Gibson’s later declaration in opposition to summary judgment acknowledged that Ms. Davis refused to accept service and disavowed knowledge of her son’s whereabouts.

Mr. Gibson eventually identified a 13537 Halley Street address in Rathdrum as Mr. Davis’s residence and personally served the summons and complaint there on July 16.

In October 2009, Mr. Davis, who had asserted affirmative defenses of insufficient service and the statute of limitations in his answer, moved for summary judgment dismissing Mr. Farmer’s complaint. Mr. Davis’s declaration in support of the motion stated:

- That he had not lived at his mother’s address on Tombstone since getting married on January 27, 2007.

- That upon getting married, he and his wife lived in an apartment in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, until the spring of 2009, when they moved to their 13537 Halley Street residence.

- That he had never authorized his mother or anyone else to accept service on his behalf.

Ms. Davis’s declaration in support of the motion stated:

- That the first process server had handed her legal paperwork without stating what the papers were.

- That she only realized in looking at them after the process server left that they were for a lawsuit pertaining to her son.

- That her son was never mentioned by the process server.

- That she made no representation she was accepting the papers on her son’s behalf.

- That she called her son about the papers but had no recollection that she ever gave them to him.

Addressing the second delivery of papers, Ms. Davis stated that the process server approached her in her yard and stated he was there to serve papers for Bradley Davis; she responded that Bradley did not live at her home and repeatedly refused to accept the papers, stating that the process server needed to serve Bradley.

Mr. Farmer opposed the motion with affidavits of his lawyer and Mr. Gibson, recounting Mr. Gibson’s information gathering and other efforts to locate and serve Mr. Davis. The affidavits stated the following:

- Mr. Gibson contacted one of Ms. Davis’s neighbors on Tombstone, who said that Mr. Davis had a boat and other personal items at the Tombstone address, that he was unsure where Mr. Davis lived, and that he did not want to get involved in helping Mr. Gibson.

- The recorded message for the telephone at Ms. Davis’s residence stated, “Hi, we’re not home right now but if you’d like to leave a message for Laurie, press 1, Brian, press 2 or Bradley, press 3”.

- Mr. Gibson’s review of “computer services” identified the Tombstone address as that of Bradley Davis and Laurie Davis and identified Ms. Davis’s residence telephone number as that of Bradley Davis as well.

- Mr. Gibson visited an apartment on Emma Street in Coeur d’Alene, an address identified by a “computer service” as an alternative short-term residence for Mr. Davis, where he was told by an unidentified tenant that she had assumed a prior tenant’s lease and had no information about Mr. Davis.

- Mr. Gibson determined that Mr. Davis received a speeding ticket on August 24, 2009 that was completed with the same Emma Street address in Coeur d’Alene where he had unsuccessfully attempted to locate Mr. Davis and despite reflecting an incorrect address, the ticket was timely paid.

From these facts and from Mr. Davis’s statements made to Mr. Gibson when served in July, the affidavits of Mr. Farmer’s lawyer and Mr. Gibson expressed their conclusions that:

- Mr. Davis received actual notice of the lawsuit and thereafter evaded service, including providing an outdated Emma Street address to the Idaho district court in connection with the speeding ticket.

- Ms. Davis’s home should be considered a second “house of usual abode” for Mr. Davis under the liberal construction of the substitute service statute.

- Mr. Davis should be judicially estopped from denying service because of his misrepresentation of the false Emma Street address evidenced by the August 2009 speeding ticket.

Mr. Davis moved to strike portions of Mr. Gibson’s affidavit containing hearsay from third parties and “computer services,” and moved to strike conclusions and opinions set forth in Mr. Gibson’s affidavit and that of Mr. Farmer’s lawyer. The motion to strike was supported by the following:

- A declaration by Mr. Davis that when cited for speeding in August 2009, the officer completed the citation using the Emma Street address reflected on his driver’s license and registration, albeit several months outdated by that time.

- With respect to the answering machine message at the Tombstone residence, Ms. Davis provided a declaration stating that both of her sons had moved out of her home prior to the first attempted service, that she now lived alone, and, “The only reason both boys names continue to be mentioned on the message is because I feel safer if it is not readily apparent to callers that I live alone. Keeping the old answering machine message was my decision, not Brad’s or Bryan’s.”

- Both Ms. Davis and Mr. Davis stated that notwithstanding the recorded message, the answering machine had never been used to take messages for Mr. Davis after he married and moved out.

The trial court judge granted the motion to strike as requested by Mr. Davis. Once this was done the service was held invalid and the case was dismissed.

Mr. Farmer timely appealed, assigning error to the trial court based on the following assertions:

- The failure to apply a required presumption of correctness to his affidavits of service.

- The granting of Mr. Davis’s motion to strike and denying his CR 56(f) motion for a continuance.

- Concluding that process was insufficient as a matter of law where Mr. Davis received actual notice and had an opportunity to defend.

- Concluding that process was insufficient as a matter of law notwithstanding his proffered evidence that the Tombstone address was Mr. Davis’s house of usual abode.

Specific Issues

- Is the address listed on a police report always correct? No

- Should a process server ask multiple questions at the door to ensure they are at the correct address? Yes

- Is it permissible to ask someone if they have a forwarding address for the target? Yes

- Is the information found through electronic databases always correct? No

- Is it important to know when a Statute of Limitations expires? Yes

- If the case is filed in Washington but served in Idaho, do Washington rules apply? Yes

Holdings

- On multiple occasions process servers ignored Ms. Davis’s comments that her son no longer lived at the Tombstone address.

- Since the time of the accident, Mr. Davis moved twice.

The Statute of Limitations in automobile personal injury cases is 3 years. - Filing the case tolls the statute for 90 days.

- Mr. Farmer’s initial service does not meet the RCW requirements for substitute service.

Reasoning

In Washington, proper service of process must not only comply with constitutional standards but must also satisfy the requirements for service established by the legislature. The fact that the due process requirements have been met is not enough. The court stated, “Beyond due process, statutory service requirements must be complied with in order for the court to finally adjudicate that dispute” and “Service of process is sufficient only if it satisfies the minimum requirements of due process and the requirements set forth by statute.” Plaintiff’s general observation that constitutional due process was satisfied by method of service “ignores specific statutory requirements for effecting service on an individual defendant in Washington”.

The statutory authorization of substitute service, provided by RCW 4.28.080(15), requires “leaving a copy of the summons at the house of his or her usual abode with some person of suitable age and discretion then resident therein.”

Mr. Farmer argues that if “house of usual abode” is properly and liberally construed to effectuate service and uphold the jurisdiction of the court as required by Sheldon, then service on Ms. Davis was sufficient, and it was an error for the trial court to conclude otherwise. In Sheldon, the court explicitly abandoned strict construction of service of process statutes in favor of the trend toward liberal construction reflected in its more recent decisions. Sheldon involved attempted service of process on an adult defendant, Sharon Fettig, at her parents’ Seattle home. Ms. Fettig had moved to Chicago for flight attendant training eight months prior to the attempted service, but thereafter maintained a number of formal and informal connections to her parents’ Seattle residence.

The evidence before the trial court as to Mr. Davis’s situation at the time service was attempted at the Tombstone address is distinguishable from the factors cited in Sheldon in every material respect. There was no admissible evidence that Mr. Davis was continuing to use his old Tombstone address for any purpose. Undisputed evidence established that since getting married, he had not lived or stayed overnight at his mother’s home. There was no evidence that Mr. Davis relied on his mother to handle business or legal matters on his behalf. While a roughly contemporaneous speeding citation was issued to Mr. Davis at an outdated address, the outdated address was for his and his wife’s former apartment, not his mother’s residence on Tombstone.

The service was held invalid and the case was dismissed.

C4PSE Comment

As far as process servers are concerned there was a lot going on with this case.

First, it is vital that you pay attention to the jurisdiction from which the documents come from verses where they are being served. In this case the documents were from Washington and being served in Idaho so Washington rules apply. Had this been reversed, that is Idaho papers served in Washington, Idaho rules would apply.

Second, ask questions. Most people are curious about why you are at their door, they will answer questions if you ask them. There was no evidence to show the process server had any meaningful conversation with Ms. Davis at all.

Finally, if you have information, use it. In this case Ms. Davis told the investigator that her son did not live with her but he served the papers anyway. Had this information been provided immediately to the client the outcome might well have been different.

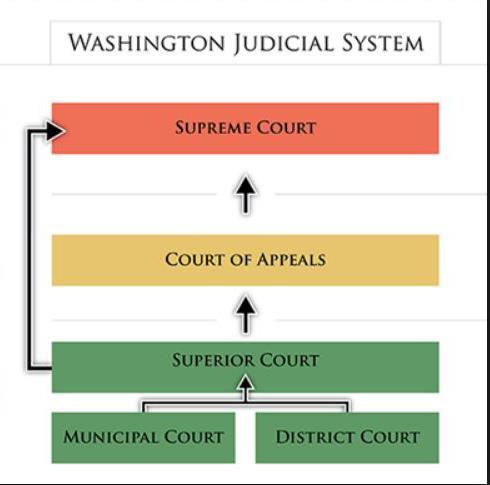

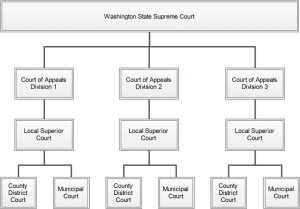

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.

This is a rough diagram of a typical courtroom in the state of Washington. Courtrooms vary a great deal from city to city and county to county but they all have the same basic structure.